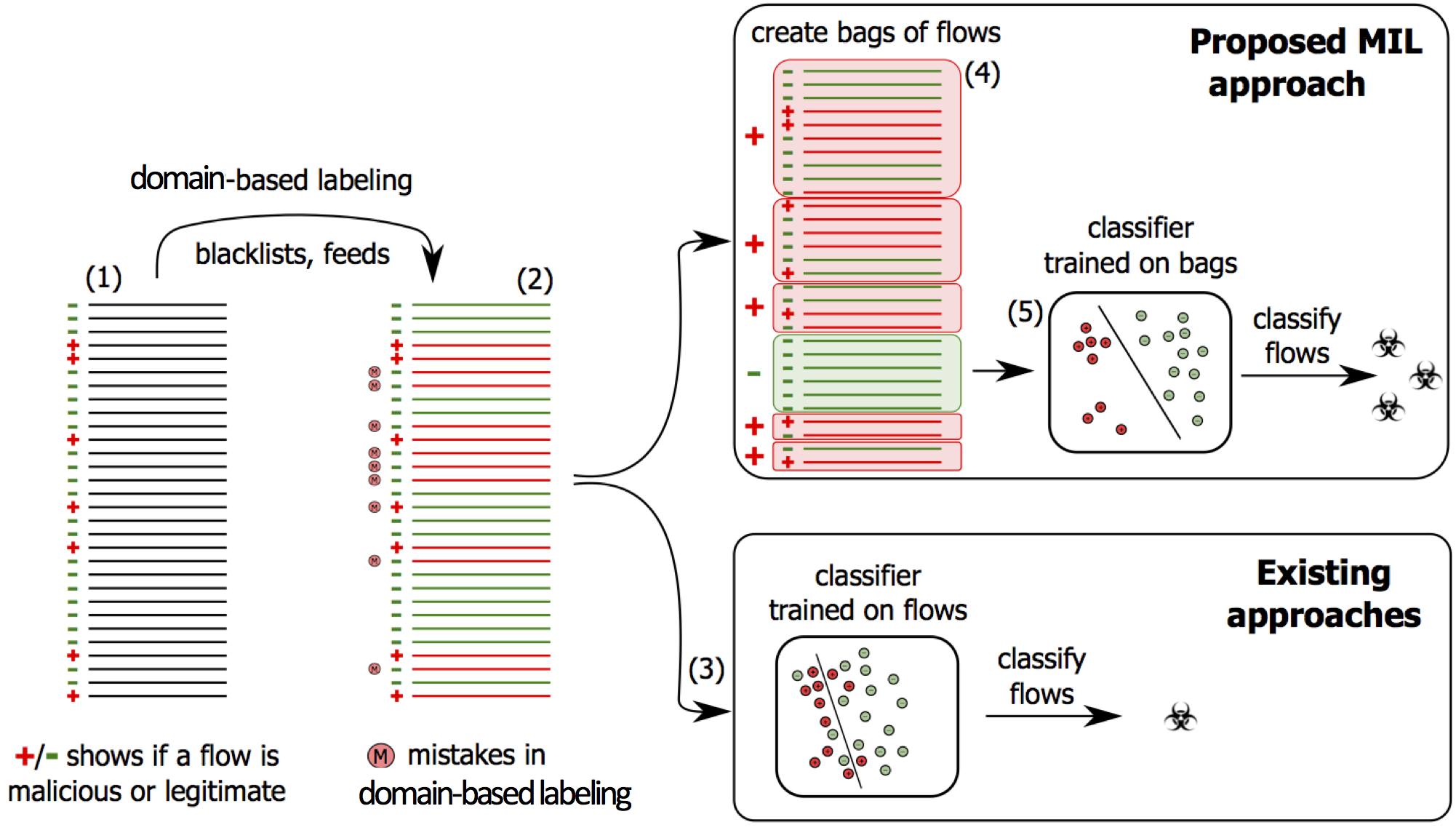

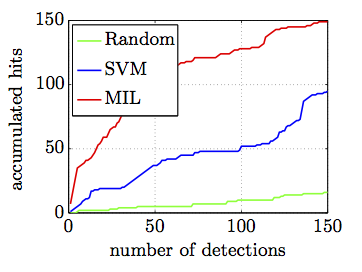

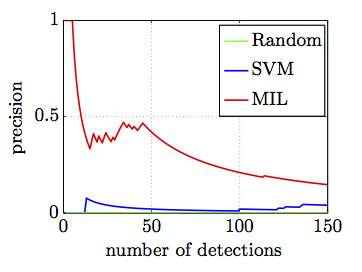

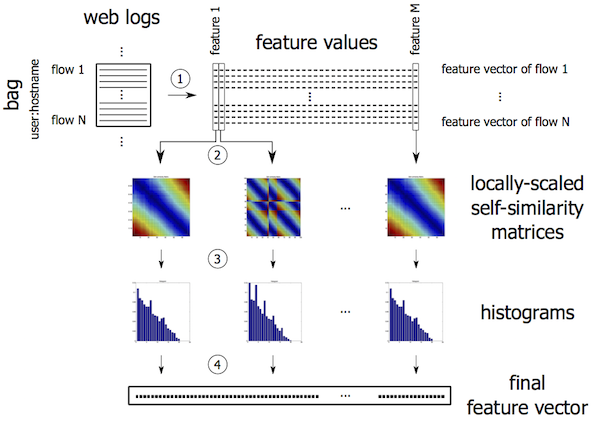

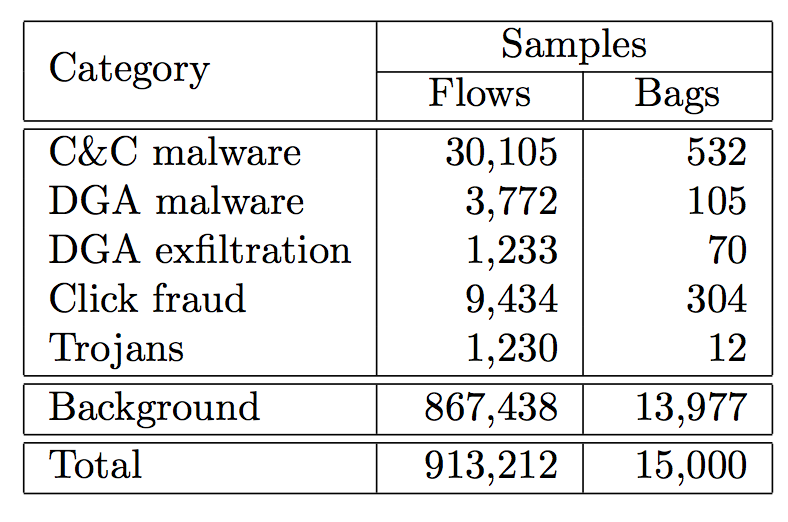

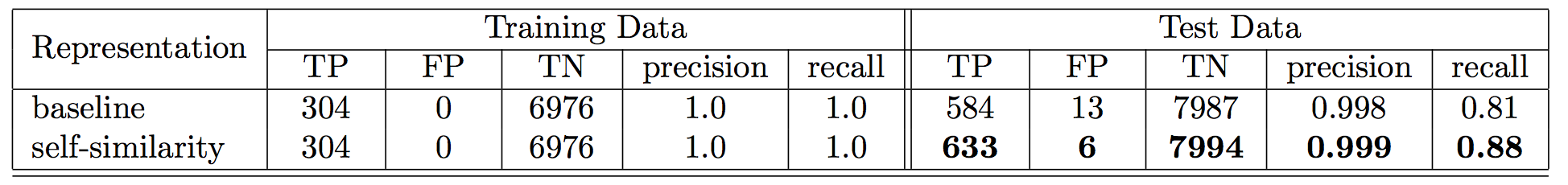

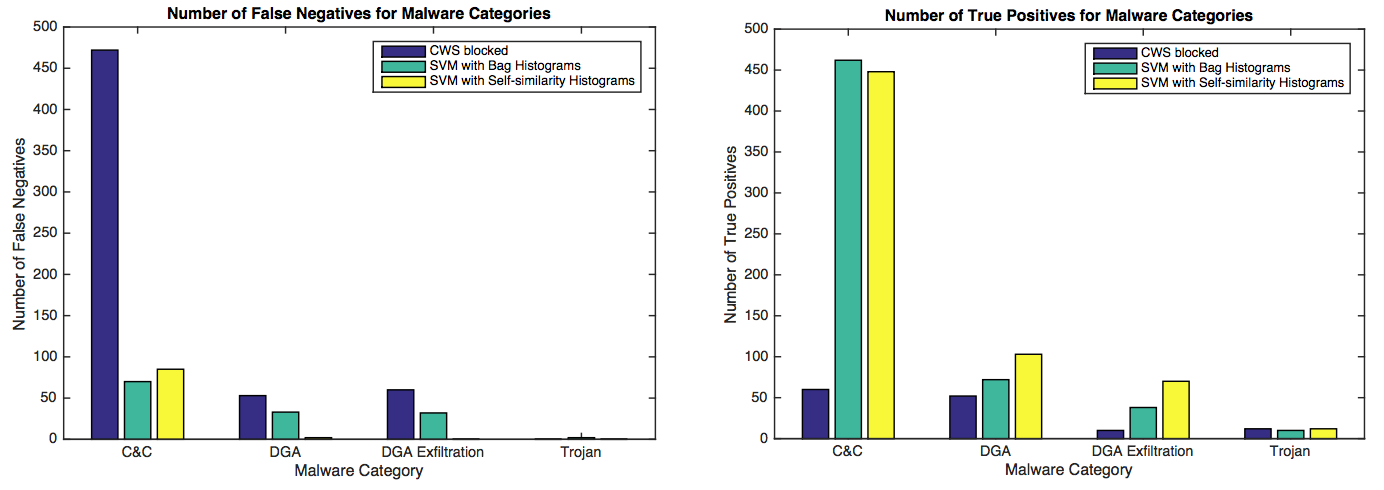

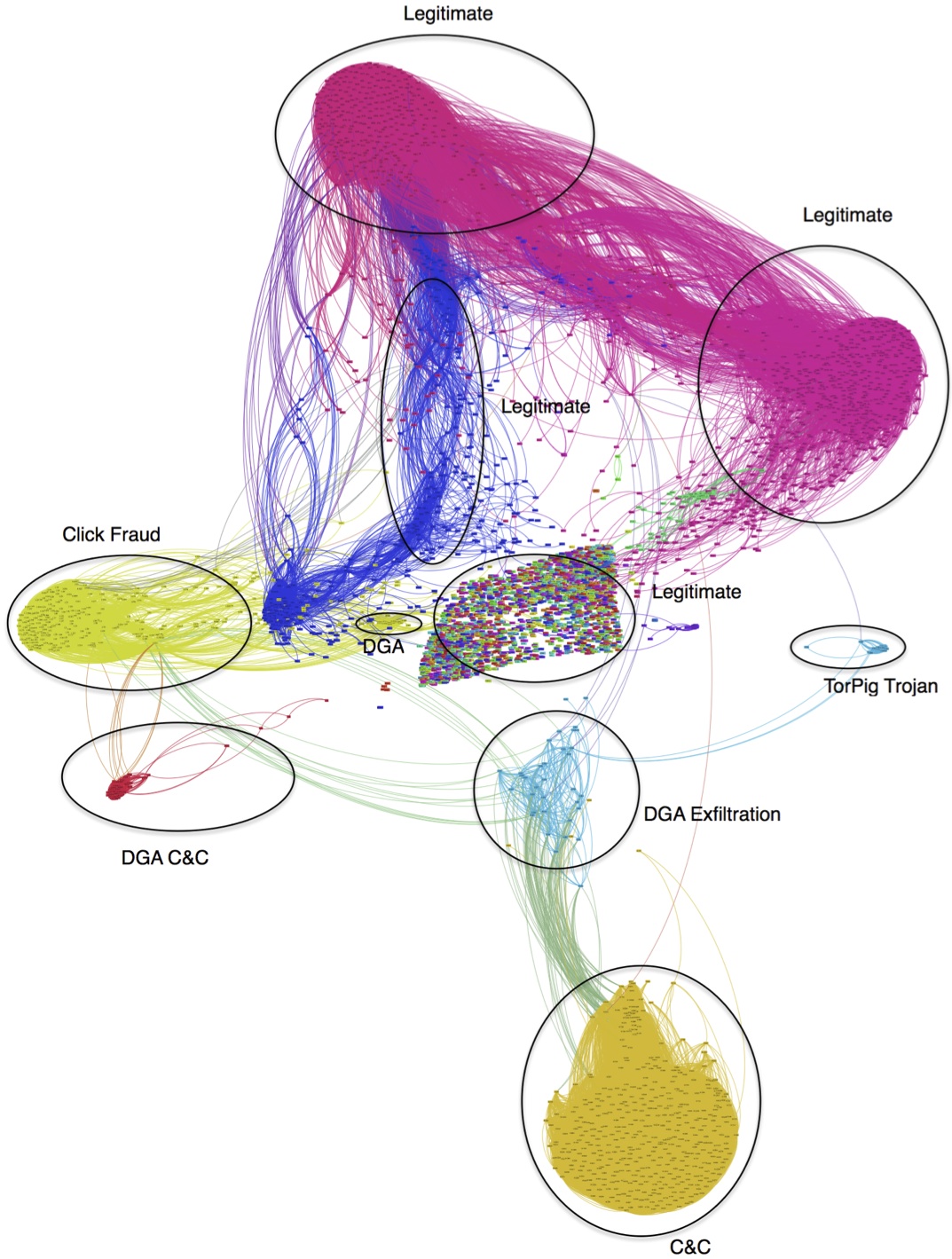

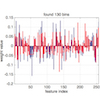

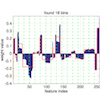

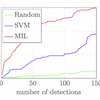

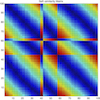

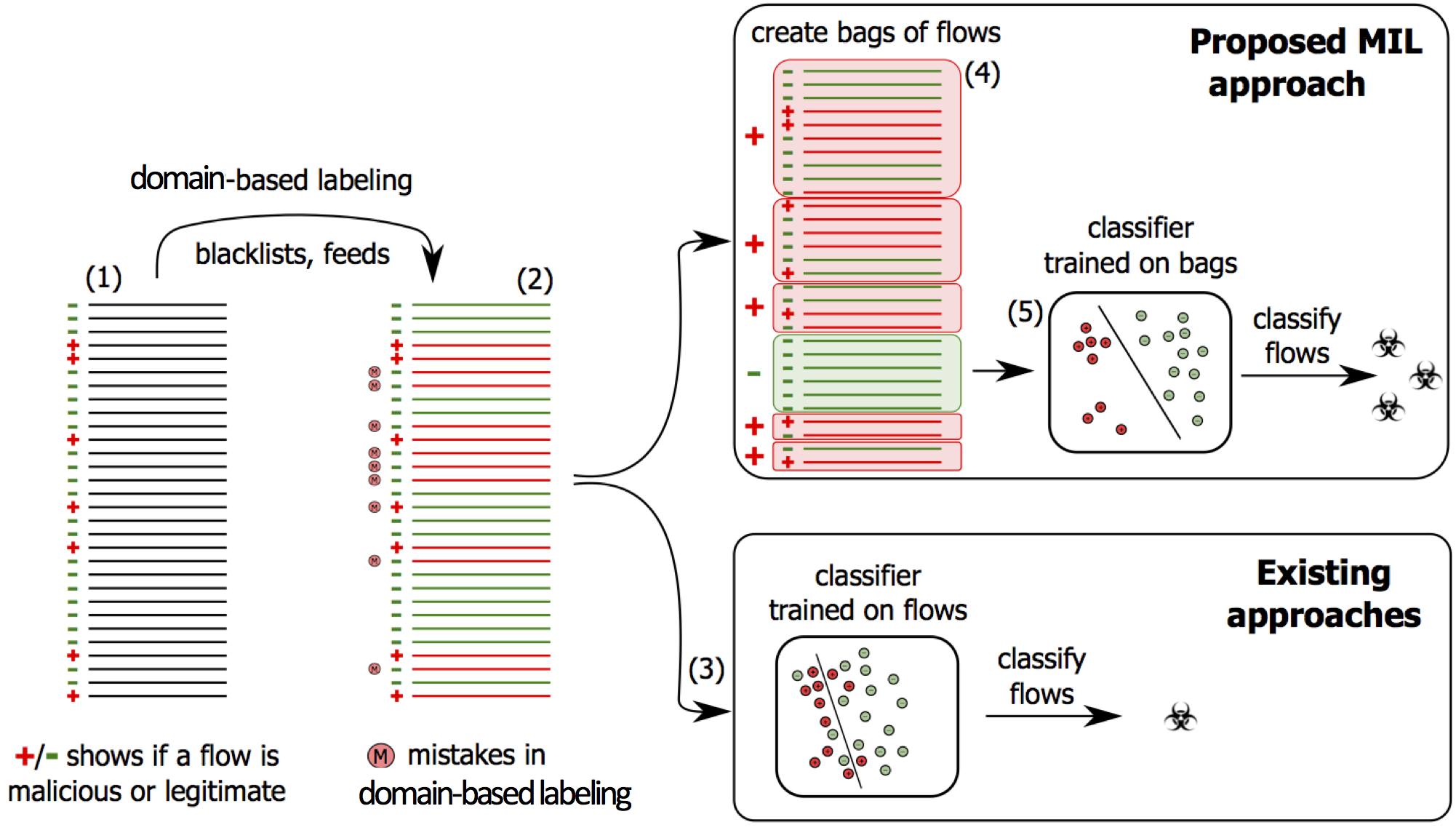

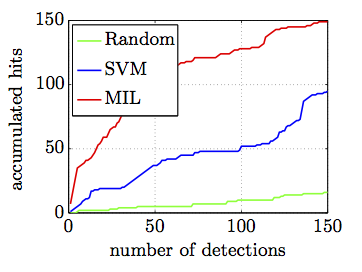

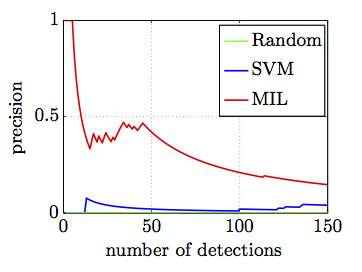

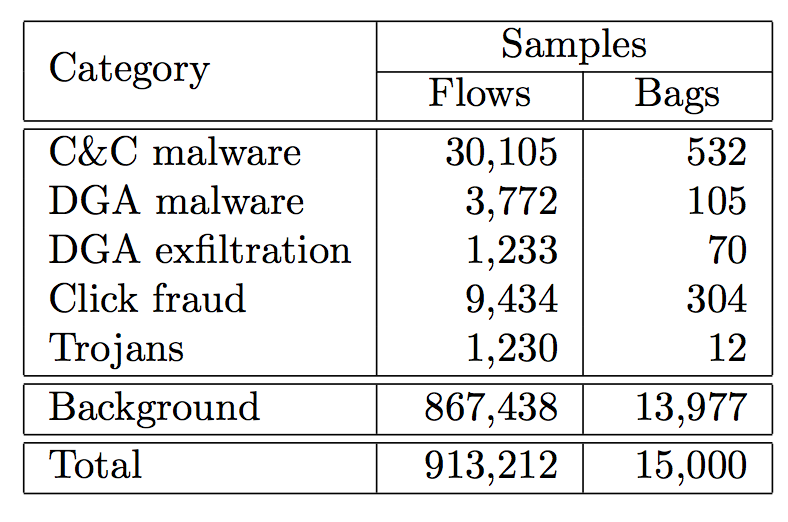

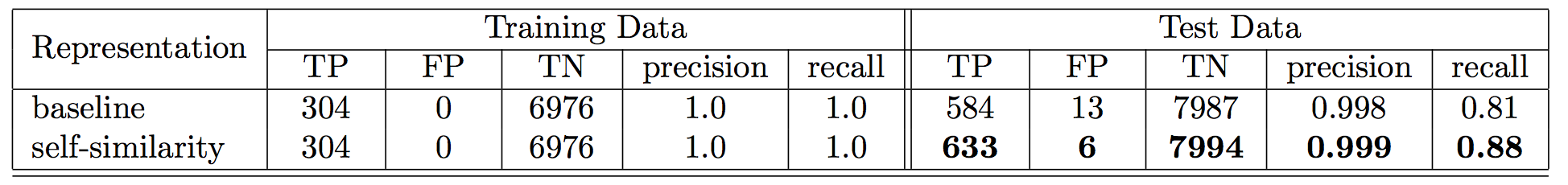

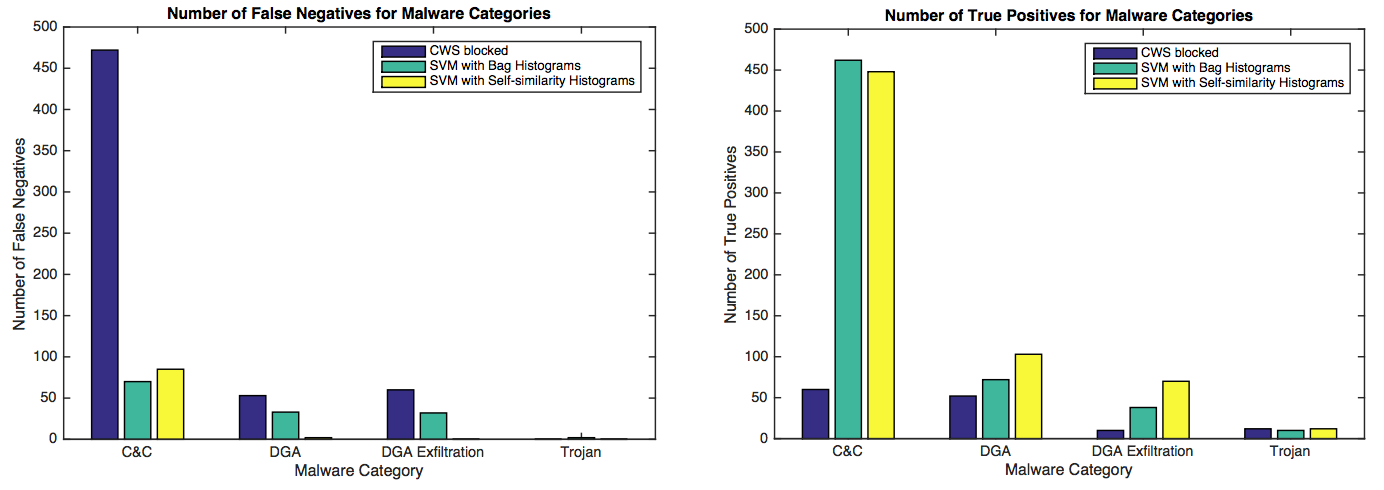

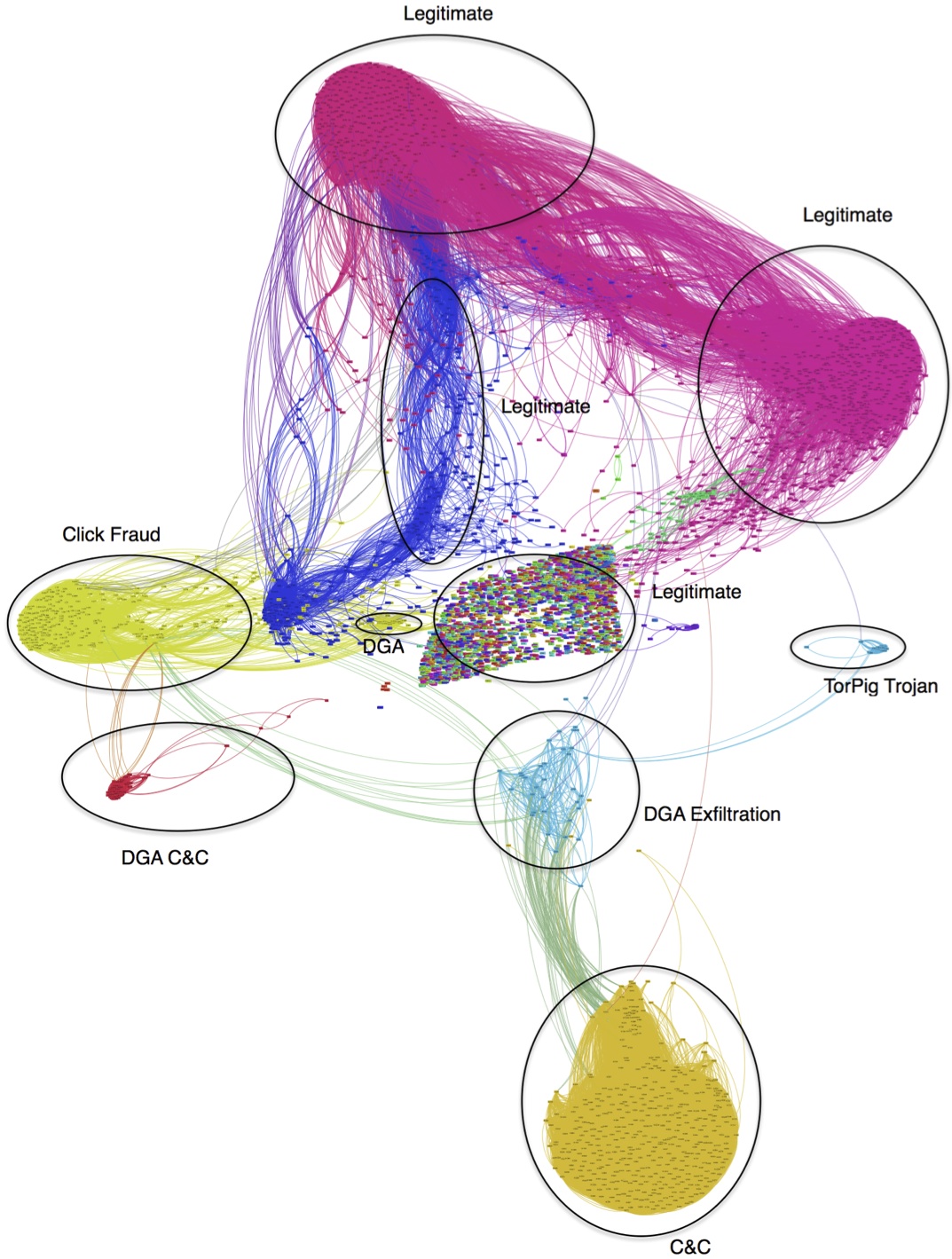

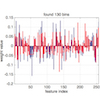

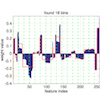

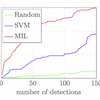

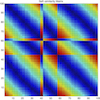

| Learning Detectors of Malicious Network Traffic This page gives a high level overview of our research on Learning Detectors of Malicious Network Traffic. Original post on the topic appeared at Cisco blog For more details, please refer to our articles published in ECML PKDD 2015 proceedings. Contents Introduction Malware is constantly evolving and changing. One way to identify malware is by analyzing the communication that the malware performs on the network. Using machine learning, these traffic patterns can be utilized to identify malicious software. Machine learning faces two obstacles: obtaining a sufficient training set of malicious and normal traffic and retraining the system as malware evolves. This post will analyze an approach that overcomes these obstacles by developing a detector that utilizes domains (easily obtained from domain black lists, security reports, and sandboxing analysis) to train the system which can then be used to analyze more detailed proxy logs using statistical and machine learning techniques. Network traffic analysis relies on extracting communication patterns from HTTP proxy logs (flows) that are distinctive for malware. Behavioral techniques compute features from the proxy log fields and build a detector that generalizes to the particular malware family exhibiting the targeted behavior. The first conceptual problem in using the standard supervised machine learning methods is the lack of sufficiently representative training set containing examples of malicious and legitimate communication. Providing security intelligence on individual proxy logs is expensive and does not scale with constantly evolving malware.The second problem is that the trained classifier is heavily dependent on the samples used in the training. Once a malware changes the behavior, the system needs to be retrained. With continuously rising number of malware variants, this becomes a major bottleneck in modern malware detection systems. Both problems are addressed by considering groups of flows (also called bags). The bags are constructed for each user (or source IP) and contain all network communication with a particular hostname for a specific period of time. Multiple Instance Learning Figure 1: (1) Flows from the training set are associated with either malicious or legitimate traffic. This fact is illustrated by a plus or a minus sign, for a malicious or a legitimate flow respectively. Unfortunately, such information is hard to obtain and is often not available for training. Therefore, a third party feeds or blacklists are used to label the training data. These lists are mostly domain-based and introduce mistakes in labeling (2), resulting in poor performance of classifiers trained on such mislabeled data, as shown in (3). Our solution uses blacklists and feeds to create weak labels of bags (4). A bag is labeled as positive if at least one flow included in the bag is labeled as positive. Otherwise, the bag is labeled as negative. An example of a bag is a set of flows with the same user and domain. The MIL classifier learns a flow-level model based on weak labels from the bags and optimizes the decision boundary, which results in better separation of malicious and legitimate flows (5) and thus higher efficacy.  | Learning of the Neyman-Pearson detector is formulated as an optimization problem with two terms: false negatives are minimized while choosing a detector with prescribed and guaranteed (very low) false positive rate. False negatives and false positives are approximated by empirical estimates computed from the weakly annotated data. The hypothesis space of the detector is composed of a linear decision rules parameterized by a weight vector and an offset. The described Neyman-Pearson learning is a modification of the Multi-Instance Support Vector Machines (mi-SVM) algorithm. The mi-SVM treats the flow labels as unobserved hidden variables subject to constraints defined by their bag labels. The goal is to maximize the instance margin jointly over the unknown instance labels and a linear discriminant function. Our evaluation of the detectors uses datasets that represent 14 days of real network traffic of a large international company (80,000 seats). The MIL detector is compared to the SVM detector learned by considering all instances in the malicious bags to be positive and instances in the legitimate bags to be negative. The Figure 2 presents results obtained on the first 150 test flows with the highest decision score computed by both detectors. The flows were automatically selected from a dataset of 10M test flows. Figure 2: The left figure shows the number of true positives and the right figure the precision of the detectors as a function of the number of detected flows. We also show results for a baseline detector selecting the flows randomly.   | The MIL detector takes advantage of large databases of weak annotations (such as security feeds). Since the databases are updated frequently, the detectors are also retrained to maintain the highest accuracy. The training procedure relies on generic features and therefore generalizes the malware behavior from the training samples. As such the detectors find malicious traffic not present in the intelligence databases (marked by the feeds). The algorithm results in a general system that can recognize malicious traffic by learning from weak annotations. Adapting to Malware Behavior Changes Next, we focus on the problem of detecting variants of malicious behaviors. The detector uses a new representation of bags computed from sample feature values. The representation is designed to be invariant under shifting and scaling of the feature values and under permutation and size changes of the bags. In the context of malware, it means that any change in the number of flows of an attack (size invariance) or in the ordering of flows (permutation invariance) will not help evade the detection. Shift and scale invariance ensures that any internal variations of malware behavior as described by a predefined set of features will not change the representation. This means that new and unseen malware variants are represented with similar feature vectors as existing known malware, which greatly facilitates the detection of new or modified malicious behaviors. The ability to detect malware variants directly improves the system efficacy. The steps for creating the representation are described in Figure 3. Figure 3: (1) Each bag is initially represented as a set of flow-based feature vectors. Bags with less than 5 flows are not processed. The representation is then transformed to be invariant against specific malware variations. (2) Shift invariance is ensured by computing a self-similarity matrix for each feature and all flows in a bag. The element (i,j) of this symmetric positive semi-definite matrix corresponds to the distance between the feature value of the flows i and j. This transforms each bag into a set of self-similarity matrices, one for each feature. Scale invariance is achieved by normalizing all values in each self-similarity matrix onto interval (0,1). (3) Size and permutation invariance is ensured by creating a histogram of all elements in each normalized self-similarity matrix. (4) All histograms for each bag are concatenated to form the final bag representation.  | We have done experiments with datasets containing 5 malware categories: malware with command & control channels (marked as C&C), malware with domain generation algorithm (marked as DGA), DGA exfiltration, click fraud, and trojans. The rest of the background traffic is considered as legitimate. The number of flows and bags in each category is given in Table 1. Table 1: Number of flows and bags of malware categories and background traffic.  | Table 2: Summary of the SVM results from the baseline and the invariant representation. Both classifiers have comparable results on the training set, however, the SVM classifier using the new invariant self-similarity representation achieved better performance on the test data.  | Figure 4: Analysis of false negatives (number of missed malware samples) and true positives (number of detected malware samples) for flow level blocks (e.g. Cloud Web Security) and SVM classifier based on two types of representations: histograms computed directly from feature vectors, and the new self-similarity histograms. Thanks to the self-similarity representation, SVM classifier was able to correctly classify all DGA exfiltration, trojan, and most of DGA malware bags, with a small increase of false negatives for C&C. Overall, the new representation shows significant improvements when compared to flow level blocks, and better robustness than the approach without the self-similarity.  | The effectiveness of self-similarity matrix capturing malware variations is shown by comparing the results to the case where the histograms are obtained directly from the flow-based feature values (i.e. without computing the self-similarity matrices). Two-class SVM classifier was trained using both representations. The training set consisted of click fraud positive bags and 5977 legitimate negative bags. The testing set consisted of bags from C&C and DGA malware, DGA exfiltration, trojans, and 8000 negative background bags. The results are summarized in Table 2 and compared flow level signature-based blocks in Figure 4. In the next experiment, the representation is used in a clustering to group malware belonging to the same category. This analysis shows how changing malware parameters influences similarity of samples, i.e. whether a modified malware sample is still considered to be similar to other malware samples of the same category. Two malware categories were included in the training set (click fraud and C&C) together with 5000 negative bags. The result is in Figure 5. Figure 5: Graphical illustration of the clustering results, where the input bags were represented with the new invariant representation. Legitimate bags are concentrated in three large clusters on the top and in a group of non-clustered bags located in the center. Malicious bags were clustered into six clusters.  | Conclusion We have shown how to use bags of flows to represent communication of malware samples. The bags can be used to train a classifier of malicious flows by computing statistical feature vectors of the flows in a bag and labeling the bags by feeds and other security intelligence. This has the advantage that the labels of individual flows do not need to be provided which makes the labeling process tractable. The MIL algorithm used in the detector training minimizes a weighted sum of errors made by the detector on the negative and the positive bags. The trained flow-based classifier has better performance than a classifier trained from individual flows without forming the bags. The entire bags can also be classified by computing a new representation that leverages all flows in a bag to capture malware dynamics and behavior in time. The representation is robust to malware variations attempting to evade detection (e.g. by changing the URL pattern, number of transferred bytes, user agent, etc.). The invariant representation is based on the idea that malicious flows in a bag will have different statistical properties than legitimate flows in another bag. This richer information makes it possible to improve the efficacy of learning-based detectors.

Publications and Further Reading

-

Bartos, K., Sofka, M., Franc, V., 2016. Optimized Invariant Representation of Network Traffic for Detecting Unseen Malware Variants. In: USENIX Security Symposium. Austin, TX, USA. Bartos, K., Sofka, M., Franc, V., 2016. Optimized Invariant Representation of Network Traffic for Detecting Unseen Malware Variants. In: USENIX Security Symposium. Austin, TX, USA. New and unseen polymorphic malware, zero-day attacks, or other types of advanced persistent threats are usually not detected by signature-based security devices, firewalls, or anti-viruses. This represents a challenge to the network security industry as the amount and variability of incidents has been increasing. Consequently, this complicates the design of learning-based detection systems relying on features extracted from network data. The problem is caused by different joint distribution of observation (features) and labels in the training and testing data sets. This paper proposes a classification system designed to detect both known as well as previously unseen security threats. The classifiers use statistical feature representation computed from the network traffic and learn to recognize malicious behavior. The representation is designed and optimized to be invariant to the most common changes of malware behaviors. This is achieved in part by a feature histogram constructed for each group of HTTP flows (proxy log records) of a user visiting a particular hostname and in part by a feature self-similarity matrix computed for each group. The parameters of the representation (histogram bins) are optimized and learned based on the training samples along with the classifiers. The proposed classification system was deployed on large corporate networks, where it detected 2,090 new and unseen variants of malware samples with 90% precision (9 of 10 alerts were malicious), which is a considerable improvement when compared to the current flow-based approaches or existing signature-based web security devices. @inproceedings{bartos:usenix16,

author = {Bartos, Karel and Sofka, Michal and Franc, Vojtech},

title = {Optimized Invariant Representation of Network Traffic for Detecting

Unseen Malware Variants},

booktitle = {{USENIX} Security Symposium},

year = {2016},

month = "10--12~" # aug,

note = {\textbf{15.6\% acceptance rate.}},

pages = {},

address = {Austin, TX, USA}

}

-

Franc, V., Sofka, M., Bartos, K., 2015. Learning detector of malicious network traffic from weak labels. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD). Porto, Portugal, pp. 85–99. Franc, V., Sofka, M., Bartos, K., 2015. Learning detector of malicious network traffic from weak labels. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD). Porto, Portugal, pp. 85–99. We address the problem of learning a detector of malicious behavior in network traffic. The malicious behavior is detected based on the analysis of network proxy logs that capture malware communication between client and server computers. The conceptual problem in using the standard supervised learning methods is the lack of sufficiently representative training set containing examples of malicious and legitimate communication. Annotation of individual proxy logs is an expensive process involving security experts and does not scale with constantly evolving malware. However, weak supervision can be achieved on the level of properly defined bags of proxy logs by leveraging internet domain black lists, security reports, and sandboxing analysis. We demonstrate that an accurate detector can be obtained from the collected security intelligence data by using a Multiple Instance Learning algorithm tailored to the Neyman-Pearson problem. We provide a thorough experimental evaluation on a large corpus of network communications collected from various company network environments. @inproceedings{franc:ecml15,

author = {Franc, Vojtech and Sofka, Michal and Bartos, Karel},

title = {Learning detector of malicious network traffic from weak labels},

booktitle = {Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning

and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD)},

year = {2015},

month = "7--11~" # sep,

pages = {85--99},

address = {Porto, Portugal}

}

-

Bartos, K., Sofka, M., 2015. Robust representation of network traffic for detecting malware variations. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD). Porto, Portugal, pp. 116–132. Bartos, K., Sofka, M., 2015. Robust representation of network traffic for detecting malware variations. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD). Porto, Portugal, pp. 116–132. The goal of domain adaptation is to solve the problem of different joint distribution of observation and labels in the training and testing data sets. This problem happens in many practical situations such as when a malware detector is trained from labeled datasets at certain time point but later evolves to evade detection. We solve the problem by introducing a new representation which ensures that a conditional distribution of the observation given labels is the same. The representation is computed for bags of samples (network traffic logs) and is designed to be invariant under shifting and scaling of the feature values extracted from the logs and under permutation and size changes of the bags. The invariance of the representation is achieved by relying on a self-similarity matrix computed for each bag. In our experiments, we will show that the representation is effective for training detector of malicious traffic in large corporate networks. Compared to the case without domain adaptation, the recall of the detector improves from 0.81 to 0.88 and precision from 0.998 to 0.999. @inproceedings{bartos:ecml15,

author = {Bartos, Karel and Sofka, Michal},

title = {Robust representation of network traffic for detecting malware variations},

booktitle = {Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning

and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD)},

year = {2015},

month = "7--11~" # sep,

pages = {116--132},

address = {Porto, Portugal}

}

|